PTSD: The Invisible Injury

“When there's a poisonous snake in our path, we freeze.

When we smell smoke, we run.

When faced with danger, fear takes over and we react, desperate to feel safe.

It's biological, primal.

But for someone who suffers from trauma, it's the everyday things: a touch of a hand, a song in a coffee shop, the smell of rubbing alcohol — ...Seemingly random, common things convincing your brain and body you're in danger, and there's no way out…”— Meredith Grey,

Grey’s Anatomy

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (known colloquially as PTSD), is a medical condition we’re hearing about more and more. What was once thought to be a mental illness only applicable to war veterans, is now known to be far more common than initially thought. After all, trauma does not limit itself to the battlefield. Trauma does not discriminate. One may find it anywhere, from a family death, to domestic abuse, even schoolyard bullying. There's no telling how the brain will react in any given situation, because our brains are uniquely ours. What may be traumatic for some, is not for others. What unifies patients is not the trauma itself, it’s the fear. Anyone who lives with PTSD will attest: this is not your average anxiety condition. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder is a monster all on its own. Few will find a single medical condition with the power to affect not only an individual’s behaviour, but also their memory, as well as causing physical pain in the body so strong it tricks the brain into thinking they are experiencing their trauma all over again.

This is a condition with enough power to permanently damage the function of the human brain. Do not be fooled, PTSD is a powerful beast.

But what is PTSD, truly? For decades, it has been shoved into the mental illness category, alongside conditions like depression and anxiety. What may surprise you is this: PTSD is not a mental illness — it is an injury.

Let’s dig deeper…

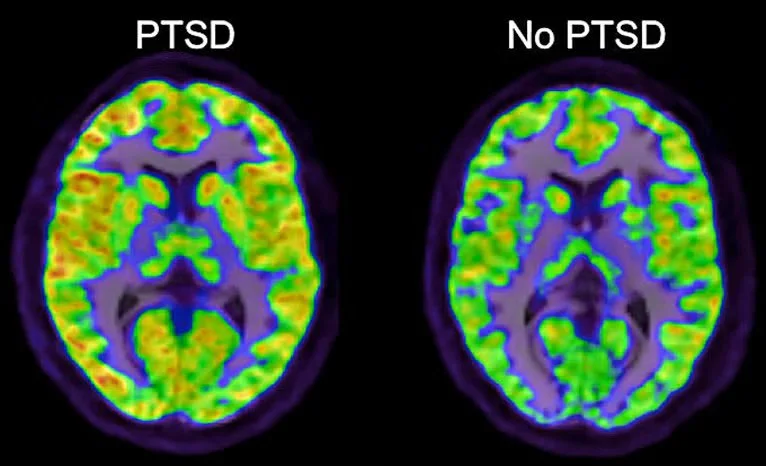

First, the frontal lobe grows quieter. This is the part of us that reasons, reflects, pauses. It’s the voice that says: “slow down. You’re safe. This moment is different”. When this region is under-active, that voice loses its strength. Rational thought no longer gets the first word. Fear does. Emotion does not build slowly, it arrives at full volume. The body reacts before logic has time to speak.

Next, the amygdala (the brain’s alarm system) burns hot. It becomes exquisitely sensitive. It scans constantly for danger. It does not rest. It does not trust. Every sound, every movement, every unfamiliar tone is processed as a potential threat. And so the body lives on high alert: muscles tight, heart racing, breath shallow, disturbed sleep… The system never powers down.

Finally, we turn to the hippocampus: the part of the brain responsible for placing memory in time. Its role is to organise our experiences into coherent chapters: the distant past, the recent past, events filed where they belong. In PTSD, this system weakens. The extent of that damage varies, because no two brains, and no two traumas, are ever the same. In my own case, the hippocampus has been significantly affected. Memories lose their timestamps. If I am asked what year I lost a family member, or which trauma occurred when I was twenty-five, I will often be unable to retrieve the date, even though the event itself remains painfully vivid.

This becomes especially difficult for survivors who try to share their story and are met with scepticism. Many trauma survivors cannot anchor certain memories to precise dates, and this is where a grave mistake is often made: their inability to provide a neat timeline is mistaken for unreliability, or worse, untruth. When the hippocampus is impaired, those carefully organised compartments collapse. Events that occurred in the past are no longer recognised by the brain as past at all. Instead, they step forward. A smell, a word, the colour of a man’s shirt — any small cue can collapse time, pulling the memory into the present as though it is happening again, here and now. We call these: triggers.

This ongoing injury to the brain helps explain why many people living with PTSD are also diagnosed with conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), depression, and chronic pain disorders like fibromyalgia. Some may also find they become ill more frequently than the average person. The reason is simple, though often overlooked: the brain does not switch off. When the nervous system remains locked in a state of hypervigilance, the body is kept under constant physiological tension. Over time, this relentless activation leads to profound exhaustion. Fatigue compromises immune function, disrupts pain regulation, and places enormous strain on the body — which is, quite literally, worn down by the effort to stay alive.

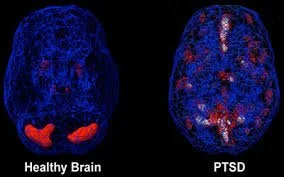

Take a look at this second image. What do you see?

A healthy brain glows evenly. Its systems communicate with one another: emotion, memory, and reason moving in quiet harmony. It can rise to meet stress, then settle back into rest once the threat has passed. People with healthy brains worry about ordinary things: what colour to paint the bedroom walls, for example.

A brain damaged by PTSD cannot comprehend stress at that scale. For us, stress does not mean inconvenience or indecision, it means survival. Worst case scenario. Life or death. Trauma. Fight, flight, or freeze. This image shows how different a PTSD brain is compared to an ordinary brain. Dimmer in some places. Scattered. Uneven. Certain regions burn too brightly, locked in vigilance, while others grow quiet. An organ meant to function as a single, integrated whole becomes divided. One part remains on guard in the past, while the present struggles to be fully inhabited. What you see here is survival etched into biology.

At last, we see proof of what survivors have been saying all along: PTSD alters the brain itself. Those who live with this injury are not “dramatic” by choice. They do not overreact for attention or effect. Their responses are involuntary, driven by a nervous system shaped by trauma. They prepare for the worst-case-scenario not out of paranoia, but because to their nervous system, the worst has already happened — and is expected to happen again. In fact, for those who have endured repeated trauma, this state can become all they have ever known; danger becomes familiar, even routine. What ends up feeling strange to them, is not the vigilance itself, but witnessing others live lives that appear untouched by trauma. The idea of a “normal” life, one without constant threat, can feel confusing, even unreal, to the PTSD brain. It does not align with what the body has learned to expect. When this reality is misunderstood or dismissed, the expectations placed on survivors become not just unfair, but illogical. To demand otherwise would be like telling someone with epilepsy to simply stop having seizures — as though willpower alone could override a neurological injury.

I believe PTSD should be understood within the traumatic brain injury framework (TBI), because it is an injury — one that occurs in the brain. If someone survives a car accident and sustains damage to the temporal lobe, clinicians readily identify that as a TBI. The cause is external, the damage is measurable, and the resulting symptoms are treated with seriousness and care. PTSD follows the same logic. Without the traumatic event(s) that caused it, this injury would not exist. The difference lies not in legitimacy, but in mechanism: the brain is injured by overwhelming threat rather than physical impact. Naming PTSD as a brain injury is not dramatic — it is medically sound. And now, more than ever, precision matters. Because language shapes understanding. It shapes treatment. It shapes compassion.

Why Language Matters…

We have seen this before. For decades, people diagnosed with depression have been told their illness is merely a “feeling”, something that can be overcome through sheer determination. This is profoundly inaccurate.

First, depression is not a feeling; it is an illness. Second, one cannot simply choose to stop being depressed any more than one can choose to stop having Parkinson’s disease or a heart condition. Third — and most disturbingly — this belief places blame squarely on the individual, suggesting that the only reason they remain unwell is because they are not mentally strong enough to choose otherwise. Suggesting this to someone living with depression is not just medically wrong; it is dangerous. Without speaking medical truth (that depression is a genuine illness involving neurochemical changes in the brain), even more people would be silenced, even more would refuse life-saving treatment, and even more would lose their lives believing they were broken, defective, or other. It is no different with PTSD. When this injury is framed as weakness, or the individual’s “instability” rather than what it is — neurological damage — survivors are left to carry not only their symptoms, but the shame of being misunderstood. The label of being crazy, unstable or a “black sheep”. And the consequences of that misunderstanding are real, enduring, and sometimes fatal.

So, now that we understand what PTSD is and what it can do, where do we go from here?

How can we best support the people we love who live with this injury?

We listen.

We respect their voice, their space, and what they tell us they need. That will look different for everyone. Some need solitude in order to feel safe; others need reassurance from loved ones that nothing has changed — that they are still seen, still loved, still themselves.

This respect must also extend beyond the personal sphere. A common misconception persists that people living with PTSD are unreliable, incapable, or too fragile to function in professional or collaborative spaces. This is neither supported by evidence nor reflected in lived reality. PTSD does not erase competence, intelligence, creativity, or work ethic. Many individuals with this injury are highly capable, deeply conscientious, and exceptionally attuned to their responsibilities.

What is required is not walking on eggshells or lowering expectations, but the same clarity, consistency, and communication afforded to anyone else. When boundaries are honoured and environments are predictable, people with PTSD do not merely cope; they contribute, lead, and thrive. Support does not require understanding every symptom or knowing the perfect thing to say. It requires steadiness. Believe them when they tell you what helps and what harms. Honour their boundaries without taking them personally. And remember that healing is not linear, there will be good days and difficult ones, and both are part of the process. Above all, do not treat them as though they are fragile or about to break. They are not made of glass — they are made of survival.

PTSD is not a feeling,

it is not a flaw of character, a weakness of will, or a descent into madness. It is an injury — an injury to the very organ responsible for memory, meaning, safety, and the brain’s ability to distinguish past from present. It is an invisible wound: one that does not appear on x-rays or scans, leaves no cast or scar, and offers no simple cure. Yet it is written into the body all the same: into neural pathways shaped by fear, into stress hormones that never fully settle, into pain systems, exhaustion, and immune dysfunction. Because it cannot be easily seen, it is often misunderstood. And because it is misunderstood, stigma remains very real.

When PTSD is understood as an injury, the way it is interpreted changes. Once it is understood that symptoms arise from changes in the brain, it no longer makes sense to judge the person morally for it. The demand that survivors should simply “move on” collapses under medical reality because their brains have been altered by trauma and therefore no longer respond to willpower alone. This injury can fracture a person’s sense of self, but that fracture is not a failure. It is evidence of what the mind and body did to survive. And when language is chosen with care and precision, we do more than describe PTSD accurately. We make room for dignity. We allow compassion. We give survivors a voice — and we create the conditions in which healing is not demanded, but finally made possible.

Disclaimer:

This blog reflects my personal experience and understanding of PTSD. It is not intended as medical advice, nor should it be used to self-diagnose. Trauma and its effects can present differently for every individual, and only a qualified medical or mental health professional can provide an accurate diagnosis or treatment plan. If you recognise aspects of yourself in these words, I encourage you to seek support from a healthcare provider who can guide you with care and expertise.